NEW YORK RADIO WIRES

November 9, 1978 - It's four AM, and on the fourth floor of

50 Rockefeller Center in mid-town Manhattan, Mike Collins, who runs the

Associated Press New York Broadcast Metro wire, is putting together the

news copy that many New York stations will use in this morning's newscasts.

The "wire" as it is called in journalism parlance, is actually a service

that delivers written stories to teletype machines sitting at dozens of subscribing

news outlets around the city. Radio and TV stations use the content

that is delivered to these machines to help form the basis of their newscasts.

The first big push of the day is the "dawn summary," a complete

wrap-up of all of the major stories from the previous day and previous night.

Content is written specifically to be read on radio or TV, rather than in

the much different traditional newspaper style of most wire copy. The dawn

summary arrives at most stations just as (or before) the morning news teams

arrive, and provides many of the stories that millions of listeners will

hear that morning over the radio and TV airwaves.

|

New York has two major wire services: The Associated Press (AP)

and United Press International (UPI). Content from these two services provides

the backbone of news information for the city.

New York is so big, has so much happening, and has so many news

outlets that both major wire services maintain special "city" wires to

carry metro news, and cater special city wires just for the broadcast market.

These metro broadcast wires provide copy written specifically for broadcast

and also move bulletins and many dozens of stories to New York area stations.

All the News and More

Beyond proving writing copy specifically for broadcast, the AP and

UPI provide a host of different services with their city wire operations,

including:

- Sending reporters to various news conferences each day held around the city

- Staffing the courts with reporters to cover judicial news

- Continually monitoring the New York City police wire

- Making police rounds in the suburban areas such as Long Island and Westchester

- Covering traffic tie-ups

- Monitoring train hotline information from Conrail and the Long Island Railroad

- Moving bulletins and advisories on metro news, even before

complete stories have been written

- Following up through the day on stories in the city

- Publishing a daily calendar "daybook" of upcoming news activities

and press conferences around the city and metro area.

|

What if these New York city wires didn't exist?

"The stations would have to do it all themselves," says Scott Latham

of UPI, "which means they'd have to hire the staff, the machines, the wires,

establish themselves with various and sundry state organizations, and essentially

put together their own mini wire service."

"Without a New York City wire," reflects AP's Collins, "stations

in New York and the Island would have to get stories that were going on

-- there would be no other way to get them -- which would be impossible to

do. They'd just miss a lot of big stories."

Original Coverage

The New York wires pride themselves on local coverage and serving

the metro area with a wealth of additional stories not only from Manhattan

but from the other four New York boroughs and also the suburbs. After the

dawn summary is out, for instance, AP turns its attention to generating new

stories, rather than simply rehashing what they've already written, and

a lot of the focus is on the outlying areas of the metro area.

"Any station on Long Island would rather have another Long Island

story and any station in Westchester would rather have another Westchester

story," says Collins, "than ... a rehash or spot summary or what the Mayor

of New York City had to say the previous day. And the city stations want

this. We've found they don't use rewrites from the wire; they rewrite stuff

themselves anyway, and they're trying to reach the suburban market as well."

And the number of stories generated is mind-numbing: "I checked on

a rather slow Monday, and found that we had moved about 80 area metropolitan

stories -- 80 different stories! That does not include tops or updates,

and maybe, with breaking stories, 4 or 5 tops with added information."

Sensitivity to Broadcast Deadlines

Both AP and UPI are also extremely sensitive to the special needs

of radio stations, which, unlike newspapers, have deadlines every half hour

or even more frequently.

|

"If we know there's been a plane crash, and we don't have enough

details to give them a full story," relates Scott Latham, ""we'll put an

advisory on the wire saying we understand there's been a plane crash, we're

looking into it, and we'll give them the bare minimum details that we have,

and we go ahead on the phones and send the reporters in to get the facts

as soon as possible."

At AP, Mike Collins, night editor Dan Murphy, and a day assistant

all have broadcast backgrounds. We've tried to be aware of the needs or radio

vs the needs of newspapers alone, which is a problem with some bureaus," says

Collins. "We know the difference between getting a story out at five minutes

before eight and five minutes after eight in the morning.

We know what morning drive is, and afternoon drive is. We know that the stations

immediately want to know about a breaking story somewhere, even if there's

only minimal information, and we won't sit on it for three or four hours

until we have every piece of the puzzle. When we know something, we try to

let the members know about it. And then even if we're not super interested

in it, they might be, because they might be in that area [where the story

happened] and they can pursue it."

Traffic & Weather

Traffic is a major component of the daily New York information diet, and both wire services provide essential commuter information to stations throughout the New York area.

"We cover traffic tie-ups, when there's something major going on,"

says Collins at the AP. "We run all train information on the Long Island

Railroad and Conrail. We receive a hotline that they operate -- and they

ring that telephone every time there's a late train -- and we file that information

on the wire. And this frees the stations themselves from having to call

the Long Island Railroad ... every fifteen minutes or every half-hour during

morning drive."

'We [also] carry the temp in Central Park, and all the forecasts

for the various zones in our area... We place a very heavy emphasis on

weather, figuring that if there's any kind of storm in the area, people

tuning into the radio want to hear that more than they do the routine thing.

If there's a big snow storm going on, they don't really want to hear what

the Mayor had to say at his news conference everyday, or what the state legislature

debated -- they want to find out if the roads are passable, or when power

might be restored, or whether the trains are still running."

Police Information

A mainstay of wire information is police news, which starts with the New York City Police Department wire, supplemented by calls to the suburban departments.

|

"We have the New York City police wire, and we have reception desk

on Nassau and Suffolk counties," says Mike Collins. "And we also have

a desk we call up in Westchester.... We make regular rounds. Also, we have

radio stations which tip us. These local radio stations have contacts in

those areas and hear about things, and a lot of times will find out about

long before we would. We've also found that sometimes local police

agencies will be more willing to talk to the local people that they deal

with everyday than to, say, the Associated Press in New York."

"As far as accuracy, most of the time they're pretty accurate, but

sometimes you get individual policemen or fire chiefs [that aren't],"

relates Collins. "We had one fire chief up in Bridgeport who told me a couple

of weeks ago that there was a double fatal fire and he told me that two

people ahd been arrested for arson murder. And as it turned out, it wasn't

correct. And so we called back and confronted him with it and he said

'Oh, really? Well, that's what I heard some guys talking about in the

building here.' That's pretty scary. This wasn't just a fireman;

this was the Assistant City Fire Chief for the City of Bridgeport."

Do police departments ever sit on something? "Very often they will

sit on something," says Collins, "and maybe sometimes it's intentional;

other times I think it's just laziness... sometimes they'll have a report

written up and they just don't feel like reading it. Other times, it'll

just be incomplete. Like they'll leave out home towns or specific charges.

And then it's up to us to track this information down. We find that

sometimes we have a release about a simple holdup that can go on a couple

of pages... and yet still leave out essential points that we need."

Straightforward Style

Despite the breezy, sometimes punchy, delivery styles of many New

York stations, AP and UPI generally play things straight.

"We try to be very straightforward and not be cute or not play games

in any way in the way we write," says Mike Collins of AP, explaining

that the AP serves all different kinds of stations including classical

stations like WNCN and WQXR, rock stations and all news stations. "We pretty

much just try to be straightforward and emphasize clarity -- make the story

clear and understandable -- and then if the stations want to be cute with

it or rewrite it or whatever, they still have that option."

Rip and Read

Perhaps one of the neatest things about working for a broadcast wire

is hearing the copy that you've written being read back to you on the radio

at work or even on your commute home.

"We will hear our stuff both on suburban stations and on New York

City stations -- both all news stations," says Collins of AP. "Especially

the first time a story breaks, they will want to get that story right

on the air. Occasionally, we've even heard our stories filed from here

on the CBS radio network, word for word. That's rare, but if it moves at,

say, three or four minutes before the hour, the station involved has a

choice of either not running it at all or going with what the wire has."

"Some of the stations that are not primarily news stations will use

our stuff. And some of the stations in the suburbs will use our stuff pretty

much word for word every time. They are spending their time developing other

stories or getting audio around the story, instead of just spending time

rewriting."

UPI's Scott Latham concurs: "On a breaking story no one's got the

time to rewrite. You must go with your latest information. If you have

a disaster such as we had at Kennedy Airport several years ago where a plane

went down, the radio station's job is to get the information out as fast

as possible, just as ours is. No one's got the time to rewrite in that kind

of situation."

"A station like WINS or WCBS -- which are all-news stations and have

a bigger staff -- will rewrite more often.," concedes Latham. "But

again, often they don't. Quite often there's no need do; why rewrite something

that says it perfectly to begin with?"

The AP News Funnel

Because of its special relationship with newspapers and broadcast

outlets, which are considered "members" rather than subscribers, the

Associated Press can pick up and share stories from any news outlet using

the AP service. This means important stories from newspapers and even radio

stations get widely dispersed via the AP service.

|

Though many stories are picked up from newspapers, AP does get news

from radio as well.

"We had, during the [1977] blackout, various people giving out information

[on the air, that we used]," relates Collins. "The mayor was on the air

live, and talking slowly, and giving out phone numbers fordifferent

services... and we took that information directly off the air and put it

on the wire."

UPI also monitors the airwaves: "We have two all-news radio stations

in New York," says UPI's Scott Latham. "They're both clients, they also

are both clients of the Associated Press. So we monitor CBS generally because

it's got network news, for two reasons: (a) to find out what AP might be

running on the wire -- if they have a story that we don't we're concerned,

and (b) also to monitor worldwide news. If we hear about something out of

Africa, we'll run over to the foreign desk, and ask them if they're aware

of that, and nine times out of ten, it's their story that went to CBS

in the first place, but it provides a dual function.

Who Gets What

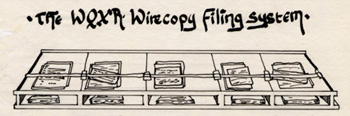

On the receiving end, radio stations are awash in hundreds of feet

of wirecopy rolling from their machines every day.

All of the larger news operations in the city get both the AP and UPI city broadcast wires. Further, most get newspaper wires in addition to the broadcast wires. City news directors say there are advantages to having both: Though broadcast wire copy is written to be read on-air, breaking stories sometimes move faster on the newspaper wires and there is usually more information on them. Newspaper wires require additional expenditures, however, because a station needs people on staff to rewrite print style into additional broadcast parlance.

Several stations get out-of-state wires. And there are police wires,

and there is a PR line as well.

Only three operations subscribe to Reuters: WCBS and WBAI get a general

NOR ("North America") wire; WBLS subscribes to the Reuters Cana-carribbean

wire which follows events in the West Indies.

WQXR is the only station to get the New York Times service wire.

Some stations get so much inbound news that the number of wires has

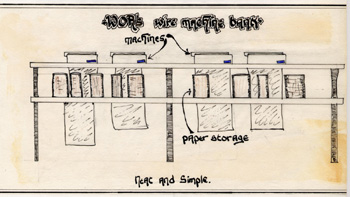

actually become an information management problem: WOR has combined three

UPI feeds onto a high-speed printer so that it doesn't have to manage three

slower wire machines.

(You can see detail of the wires that each station subscribes to in 1978 by visiting the "datasheet" overview for each station in this documentary.)

Daybooks and Nightbooks

The "daybook" is a daily calendar of upcoming news events such as

press conferences, mayoral staff meetings, and high-profile court cases.

New York City Daybooks are offered by both AP and UPI, and both services

also provide a smaller "nightbook" chronicling upcoming evening activities.

News directors use both daybooks and nightbooks, in combination with newspapers'

stories and calendars, to figure out where to send their reporters.

The AP's daybook runs first thing in the morning, and the nightbook

moves around 1 PM. You can see a complete example

of a daybook from the Fall, 1978 on this web site.

"[The daybook] includes events news conferences, and anything we

feel radio stations and the television stations might want to cover,"

explains AP's Mike Collins. "Whenever possible we include telephone contact

numbers so they can call and maybe get some information on the phone or

get audio on it if they can't afford to send a staffer over. Many organizations

call us. Government agencies have come to know that the wire services are

one place where they can immediate reach every station in town. Also,

we get news releases from various government agencies, and from private companies

and also from going through the newspapers.

While most stations have at least the rudiments of a futures file,

news directors use the daybooks extensively. WXLO's Charlie Steiner calls

them "wonderful!" WABC's Paul Erhlich says they're a station's "eyes

and ears."

There are dissenting opinions, however: WPIX's John Parsons sees

the city's reporters following daybooks as a covey of partridges would follow

a trail of seed: "It tells you some of what's going on," Parsons concedes.

"but its clients are usually politicians and people involved in the news machine,

who know there is a daybook in existence and so alert the wire to so-called

'events.' If you use that as your Bible, then you're not inventive,

and you are not enterprising, and you are not talking to people."

Parsons believes the daybook can only be used effectively as a 'tip

sheet' -- a clue to some of the things 'going on in town.'

Still, Parsons is in the minority; most station news directors rely

on the daybook heavily to plan their coverage for the day.

What Makes the City Wires So Special

New York's News Directors revere the city wires for the wealth of

information they provide minute by minute during the day's crucial drive

times, and for the tools they provide in helping news departments cover

the city. Many, who have worked in other cities outside of New York, are

in awe of the special services provided in New York City, which is one of

the few cities in the world where city wires are available.

"[The metro wire in New York] is unusual because the subscribers

to UPI's wire come from a highly localized area, and they are therefore

interested in highly localized news," explains Scott Latham of UPI, "whereas

a state wire will have its clients spread out over an entire state, and

therefore is interested in a wide variety of news. New York City, for instance,

doesn't really care too much about what the grape growers of Western

New York are doing. Conversely, the New York grape growers don't care too

much whether a bank got robbed on 42nd street, and that therefore should

not appear on the state wire, unless it were a major holdup which everyone

would be interested in."

Mike Collins of the Associated Press agrees: "We're in a special

situation here. We have New York City radio stations which aren't really

looking for rewrites, and suburban stations which are not looking for

rewrites. In other situations -- for example in Connecticut -- where you

have 45 radio stations we found the stations up there did use the rewrites.

Many of them are very short-staffed and had disc jockeys who were just

ripping the wire. So this [New York] wire is pretty unique. But so is the

market."

And Collins tries to keep in touch with the special requirements

of his customers by talking to them a lot.

"The basic philosophy under which we have operate is to try to be

as much use as we can to any newsroom both in the city and in the suburban

areas. And we've tried to be very sensitive to... the ideas that these

radio stations have, and try to remain in close touch with them and see

what they have to say, because really, that's why we're here."

- 30 -

See Also:

An Associated Press 'Daybook' - Visit a complete daybook from a fall day in 1978.Visit New York stations - Back to the home page to visit more stations' news departments.

Elsewhere on the Internet:

The Associated Press -

The official site of the Associated Press.

United Press International

- The official site of United Press International.

About this report

This research documentary is Copyright 1979, 2003 Martin Hardee - All Rights Reserved. (read more...) Material may be quoted or excerpted for non-profit research purposes without additional special permission. For additional information email martin @ hardee.net.